[While writing an earlier post about volcanoes and tasting ash, a memory flashed of another time and place where I tasted the grit of ash, and my mind wouldn’t let go. I wrote this before I learned that January 27, 2020 was the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. While this is simply my story, some stories are meant for us all.]

July, 1977.

Oświęcim the road signs read in Polish. Auschwitz. We had been driving through farm fields which ran right up to the compound fence. The parking lot gave us the iconic view of the gate with its arched Arbeit Macht Frei sign. Walking into the Visitors Center, which used to be the administration building, I was disappointed. It seemed a bit rundown, dingy and dark.

One of my companions explained that the only reason the site was a museum at all was because the Soviet Union insisted. They had lost some 20,000 soldiers there. Naturally, the movie shown at the Visitors Center put a great deal of emphasis on the liberation of the camp by the Soviet army. But it also did nothing to gloss over the atrocities that had occurred or the horrible conditions the people were found in.

After the movie, our small group split up to wander as we would. I decided to leave the gas chambers and ovens for last, and headed towards the cell blocks, which were built like two-storied barracks. Some had been converted to displays. I walked through a block that was cleaned of all textiles and debris, but made it clear how overcrowded the people were, sleeping four or six to a wood-plank bunk.

Other cell blocks had been refurbished to house huge displays behind floor to ceiling glass, some stretching 15 or 20 feet long. Eye glasses in one. Prostheses in another. Human hair and the cloth made from it, sold as horsehair. Clothes. Shoes. Other displays were smaller but no less horrific. Lamp shades and other articles made of human skin tanned into leather. Ledgers full of names. Thousands and thousands of names.

There were cell block buildings that hadn’t been opened since they were closed on the day of liberation, some 33 years prior. Peaking through a dirty window, I saw nothing but darkness beyond the timber of a bunk-bed post.

I finally found myself at the corner where the interrogation block was. Block 11. Unlike the open barracks-style units of the same size, this building was broken up into various rooms. A couple of offices. Interrogation rooms with medieval-style torture machines. Cells. The one I walked into had a barred window with a view of the execution yard and firing wall. There was no furniture, no special features built into the plain walls.

The walls themselves were covered in graffiti. Names, dates, hash marks. A few were in ink of some sort, but the vast majority had been painstakingly etched into the walls themselves. So many that they overlapped one another.

How many people had been in this room, waiting for their turn at questions and torture? How many had waited here for the summons to the adjacent courtyard and execution? Certainly not all the millions who were gassed and cremated. This was for the soldiers and anyone else who might have valuable information on troop movement, the various resistance groups, or how Jews were being smuggled out of Nazi territory. Or those who broke camp rules, but didn’t warrant immediate death — examples to any others who maintained hope against all odds. Hundreds? Thousands? I could almost hear their whispers of agony, despair, longing.

I followed the other visitors downstairs, where there were more cells, darker than above, lit only by tiny windows near the ceiling. At the end of the narrow corridor were the Standing Cells. Measuring one meter square, prisoners were forced to crawl in through a small entry at the bottom and stand throughout their confinement, which was shared with at least 3 others. [Wikipedia says they held four prisoners each; I recall the information on site saying it could be six, prisoners being so emaciated.] Breaks were supposed to take place but were generally non-existent. It wasn’t unusual for someone to die in the cell and be dragged out.

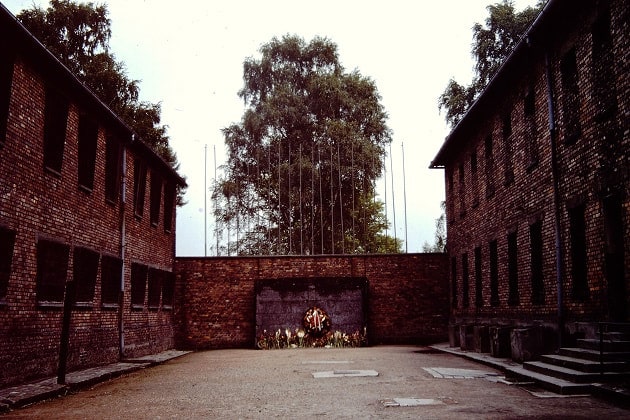

The next thing I recall is standing outside the gate to the execution yard, which was in between the interrogation block and the medical block (where Mengele conducted his experiments). There was a wreath of flowers in front of the brick wall where prisoners were executed by firing squad. The flowers were red and white with greenery. Simple. Stark.

I stood there for some time, staring at the flowers. Breathing in the outside air dusted with ash on the occasional gust. Thinking or not thinking; I don’t really know.

I returned to our vehicle without stopping to see the gas chambers or the ovens. I didn’t need to. The tall berm of ash that separated them from the other buildings was enough.

Five months later:

I was in Jerusalem. Our tour group had stopped to visit the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial. I walked in, and it was totally different from Auschwitz. Light, bright and airy. The displays were tasteful, respectful and informative. Ledgers under glass, pictures of the displays I had seen with a few samples next to them. I told my friend, “I’ve seen this before; I’ll just wait outside.” Yad Vashem, of course, isn’t just about Auschwitz. There were also Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Ravensbrück, and many others. But I sat on the side of the fountain outside, fighting tears, trying not to think and pretending to soak up the sun.

Two years later:

For a Writing 101 assignment, I wrote about my visit to Auschwitz. I discovered two things at that point: I really hadn’t thought or talked about it much since coming home, and I couldn’t remember leaving the basement of Block 11.

At that time, it was still fresh enough that I could remember almost every step, what order I saw everything in. But I couldn’t remember getting outside. I still can’t. I’m sure I walked out silently like everyone else, but I could have been screaming and raving for all I know. One thing I was certain of: I had encountered evil.

That was my first inkling of how deeply the event affected me.

A Sense of Place

It was a few months later in Israel that I realized I have what I call a sense of place. Some places have a presence, a sacredness that resonates deep within me. I’ve felt it in the desert wilderness of the western U.S. where people have been few and transient at best, where the earth itself breathes time. And among the giant trees in the Olympic Rain forest, full of life both new and ancient.

But I have mostly felt it in ancient places where people lived, and worked, and died. At a 1200 year old monastery outside of Vienna. At Tel Lakhish, where the Assyrians killed so many Judeans that a layer of dirt is still stained with their blood to this day. At some Anasazi sites abandoned centuries ago.

I realize now, I had felt it at Auschwitz. But that was the first time I felt the “ghosts”. Not spirits so much as the echoes of Pain. Sorrow. Cries for help. Injustice. Despair. And yes, Evil.

Did that experience awaken something within me? Maybe, but I don’t think so. I think it was there all along; I just hadn’t learned how to listen yet.

It’s been forty-three years now.

But as you can see, that one day changed me in ways I still haven’t fathomed. Yes, I’ve encountered evil since then, but not to that depth or scale. Not that it doesn’t exist today — just look at the headlines. Genocide, ethnocide, and forced labor still exist and occur around the world. I just haven’t encountered them personally.

But, perhaps what stands out to me today as I look back is — of all things — hope. People survived. Battered, broken in body and soul, yet some survived to tell the tale. To remember the lost. To remind us, not only of the evil, but that it is possible to go through hell and come out the other side.

With the fall of Communism and the Iron Curtain, it’s easier to travel to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland. From the pictures I’ve seen, some of the museum amenities have been improved, while some of the buildings have decayed beyond repair. If you have the chance to go, do so.

Some things should not be forgotten.

It’s difficult to grasp the concept of evil until you encounter it. Especially when it doesn’t slap you in the head like gunfire but is insidious, worming its way into your thoughts with rationalizations and excuses.

Perhaps it is necessary to face evil in order to understand that it can be fought. It can be defeated: with careful thought, goodness, grace and hope, and time and effort — and prayer.

But if evil is simply ignored, it has already won.

just a thumb’s up – nice essay

Thanks